Kierkegaard’s debt to Pietism

Can we call Søren Kierkegaard a Pietist? Labels don’t stick easily to a solitary individual like Kierkegaard. Even though his methods and goals were nothing like Spener’s or Francke’s, this essay makes a case that there are some strong similarities between Kierkegaard’s writings and the Pietist awakening that transformed Protestant Europe. Both Kierkegaard and the Pietists took a subjective approach to God and truth. The Pietists and Kierkegaard stressed conversion, daily devotional reading, and personal piety. Neither Kierkegaard nor the Pietists wanted to reform Christian doctrine so much as they wanted to reform individual lives. The Pietists were critical of the institutionalized church and the government functionaries who served as ministers, while Kierkegaard attacked Christendom and called its clergy “cannibals.” Kierkegaard and the Pietists were inspired by mystics such as Thomas à Kempis, Bernard of Clairvaux, and St. Hildegard. Kierkegaard was a unique genius, but he was clearly riding the current of the Pietist movement.

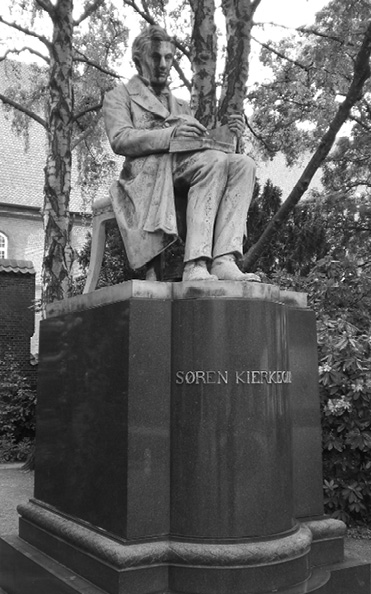

Kierkegaard statue, Royal Library, Copenhagen. PHOTO: Mark Safstrom

I. Kierkegaard’s Background in Pietism

Pietism was alive in the Kierkegaard family long before Søren was born. Søren’s father Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard grew up on the buckle of Jutland’s “Herrnhut belt.” The Herrnhuters were Moravian Pietists, spiritual children of Count Von Zinzendorf. The Herrnhuters kept nominal ties with the official Lutheran state church of Denmark, but their worship tended to be more emotional, anti-intellectual, and aimed at personal conversion. German Pietism became moralistic after Franke, but the Herrnhuters emphasized grace. Like many Herrnhuter children, Michael struggled to hear this message of God’s grace in the constant call for conversion.

Michael turned his back on the pious lessons of the Moravians before moving to Copenhagen when he was 11 years old. While he was supposed to be tending sheep out on the cold and miserable moors, Michael climbed a hill, shook his fist and cursed God. For the rest of his days, Michael would regret his childish behavior in Jutland. He was convinced that God was punishing him for his youthful rebellion by demanding the lives of his children while they were still young. Only two of Michael’s seven children lived beyond age 33. Michael passed on his fear, his melancholy, and his dreadful view of God to his youngest child Søren.

When Michael arrived in Copenhagen, he returned to the comfort and kinship of his Moravian Pietist roots. He immediately joined the Herrnhuter Congregation for their Sunday evening services. On Sunday mornings he worshiped in the official state church of Pastor Saxtorph, “the only Herrnhuter and most confirmed Pietist among the official clergy of Copenhagen.”1 By the time Søren was in the family picture, the Kierkegaards spent their Sunday mornings worshiping with the “anti-rationalist” preacher J. P. Mynster, and then attending Pietist lay meetings in the evenings with the Congregation of Brothers.

We may question whether Søren Kierkegaard remained a Pietist, but there is no questioning that he was a child of Pietism. The most influential person in his life, his father Michael, was a leader among the Copenhagen Pietists. As the Moravian Congregation of Brothers outgrew their meeting hall, it was Michael who led the new building campaign. Søren did not carry on his father’s devotion to the Moravian movement, but his early faith was rooted in Pietism.

Kierkegaard did not join the Moravians as an adult, and there is no evidence he even considered doing so. What mattered most to Kierkegaard was not whether someone subscribed to certain denominational doctrines or joined a specific group, any more than, as the pseudonym Johannes Climacus bitingly remarks, whether one adopted a new hymnal. The side of Moravians that appealed to him was less what they believed than how they put their beliefs into practice. He was attracted to the Moravians not by their books of theology but by their lives.2

Just as today’s children of the evangelical movement may hold onto faith while rejecting the term “evangelical,” Søren Kierkegaard kept his father’s faith while leaving the Moravians. Kierkegaard chose not to be weighed down by a commitment to the Moravian subculture. His own personal “leap of faith” was just as heartfelt and nonrational as any Pietist. Kierkegard’s wandering away from the Moravians is vintage Pietism. He prioritized his personal experience and subjective faith above membership in a religious organization.

II. Kierkegaard’s Readings in Pietism

Kierkegaard’s library was well stocked with books about Pietism and religious works written by Pietists. Just as you can’t judge a book by its cover, you can’t fairly judge a reader by the books in their library. Some of his editions were likely handed down to him by his Moravian father. The secondary sources he had on Pietism were often critical of the movement, while the primary sources on his

shelves by Johann Arndt, Philip Jakob Spener, Johannes Gerhard, Christian Scriver, Gottfried Arnold, and Gerhard Teerstegen helped inspire the Pietist awakening. So we must turn to what Kierkegaard wrote about the Pietists to understand his sympathies and criticisms.

Kierkegaard placed great authority upon Johann Arndt, the spiritual grandfather of Pietism. Early in his career, Kierkegaard condemned the overly emotional contemplation of the wounds of Christ in order to conceive what sin means to God. After reading Arndt, Kierkegaard changed his mind and even explored the mystical practice. Kierkegaard followed the pattern of Arndt who challenged his contemporaries to give living expression to their faith. Kierkegaard called Arndt’s book, “an old, venerable, and faithfully edifying work.”3 Of the man himself, Kierkegaard heaped the highest praise calling him, “simple and moving.”4

If Arndt is the grandfather of Pietism, Pietism’s father is certainly Philip Jakob Spener. Kierkegaard read Spener and the secondary works on Pietism and Spener popular in the day. Clearly Kierkegaard understood Spener’s pious desire for a re-awakening of Christian faith and action. What is not quite as clear is his assessment of the man. He writes, “When Spener made his appearance, the established church was strictly orthodox, and Spener was charged with heterodoxy. Now Pietism is the only little stronghold orthodoxy has, the established is half-and-half.”5 Kierkegaard celebrates the orthodoxy of the Pietist movement, but his comment on Spener serves primarily to criticize the established church.

Far more telling is Kierkegaard’s assessment of Spener’s successor, August Herman Francke. When Francke took leadership of the Pietists in Halle, there was a noticeable conservative shift. Rather than just focusing on the reawakening of the heart, Francke stressed external signs of faithfulness such as refraining from dancing, emphasizing the sanctity of the Sabbath, and perhaps most irritating to Kierkegaard, the eschewing of social amusements such as the theater. In his personal papers, Kierkegaard writes,

Francke observes correctly (in connection with dancing, to which, incidentally, he is opposed) that such matters are not primary subjects for discussion; the most important thing is the improvement of the heart. But the world prefers to talk about such things first, in order to label Christianity as extremism.

But Francke himself does not actually use the approach properly. He goes into the subject of whether dancing is permissible and gives reasons against it. No, it is actually a more sagacious approach to answer: I am so far behind in Christianity that I do not have the time to get involved in the question of dancing, or to dance, either. This is an authentic religious approach. The trouble is we are so inclined to show that we are right and to come up with reasons, and thereby we abandon the essentially Christian position.6

Among the reasons against dancing Francke gives there is one which is so lofty or high that one almost has to laugh — he says that dancing conflicts with the “imitation of Christ.” No doubt a dancing partner really does not look like an imitator of Christ, but here, as we say of the voice, Francke’s argument breaks into a falsetto; it is too high.7

Francke was so desperate to be right about dancing that he left the simple truth for an extreme argument. This intellectual dishonesty was unacceptable to Kierkegaard. He skewers Francke’s inauthentic approach to matters of personal morality and thereby exposes his own problem with the Pietists. Kierkegaard wasn’t interested in a cultural crusade against worldly pleasures when the whole of Christianity was crumbling all around him. Why should the individual believer be concerned about the dancing habits of her neighbor when Christendom had compromised with the world? Elsewhere in his journals Kierkegaard is more positive towards Francke, but he would never abide with external morality taking precedence over inward conversion.

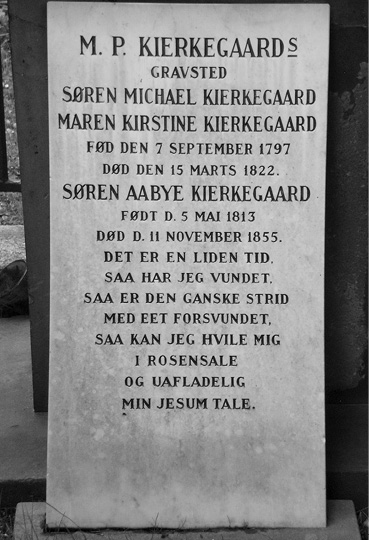

Kierkegaard family grave, Assistens Cemetery, Copenhagen. PHOTO: Mark Safstrom

More than any other Pietist; more than any other writer, Kierkegaard revered the poetry, songs and lay sermons of Pietist and mystic Gerhard Tersteegen. Tersteegen was not a theologian, or even an ordained pastor, but he had great authority with Kierkegaard. Kierkegaard could see “inner truth” in Tersteegen. As Thulstrup puts it,

Tersteegen was the object of the greatest recognition that Kierkegaard ever expressed: “On the whole Tersteegen is incomparable. In him I find genius and noble piety and simple wisdom”…. Kierkegaard never expressed such recognition and admiration of any other of his favorite authors; Socrates was wise, Brorson and Johann Arndt old and venerable, but Tersteegen overshadowed them all.8

When Kierkegaard was close to bowing to his father’s wishes and finding gainful employment as a minister in the State Church of Denmark, it was the writings of Tersteegen and the mystic Fenelon who turned him around. Kierkegaard was inspired by a Christmas homily written by Tersteegen about the Magi changing direction at the call of God. Abandoning compromise with his father and the church, Kierkegaard committed to pursuing a life of “decisive religious existence.” Kierkegaard kept returning to Tersteegen for guidance and the courage to turn faith into action.

Thulstrup names four writers that Kierkegaard held in the highest esteem: Socrates, Arndt, Tersteegen, and Brorson. Three were embraced by the Pietist movement. You can’t judge a reader simply by the contents of their library, but the Pietists were not just filler on Kierkegaard’s shelves. Arndt and Teerstegen in particular had authority over Kierkegaard. We can learn something about an author and thinker by considering who their favorite writers were and the authority that was granted to them. We now turn to the poet and hymnwriter Hans Adolph Brorson to consider the depth of Pietism’s influence on Soren Kierkegaard.

III. Kierkegaard’s Singing in Pietism

There is something about the songs of our childhood that stick with us until the end of our days. Any retirement home chaplain can tell you that when the elderly forget everything else, the songs of their youth are still accessible. It’s as if the songs are written on our hearts where Alzheimer’s and extreme old age cannot reach them. While Kierkegaard left social conventions and his religious communities behind him, he could not leave the songs of his youth. The old Brorson songs that Kierkegaard grew up singing with the Moravians always had influence on his faith and his writing.

Brorson was one of Denmark’s most celebrated hymn writers. Brorson spent his life and career in the Lutheran Church of Denmark. His father was a Lutheran pastor, and Hans rose to the office of bishop. Brorson also grew up in the 18th century awakening of Denmark

and he was quite sympathetic to the Moravians and the Halle Pietists. Even when his duty as a representative of the state compelled Brorson to enforce limitations on the freedoms of the Moravians, he wanted to be on good terms with the Pietists.

While serving as an assistant pastor at a bilingual church, Brorson took on the task of translating popular German Pietist hymns into Danish. He also tried his hand at writing some of his own heartfelt hymns. Brorson discovered that he had a gift for poetry and expressing piety and faith. His songs became popular with all the people of the awakening including the Moravians.

Kierkegaard would have learned Brorson’s hymns by heart as he sang in Moravian “song services.” The Moravians have a peculiar take on the hymn sing. They bypass the sermon for a series of carefully chosen fragments of popular hymns. The Moravians learned to pick up on the song being referenced and they start singing together without the benefit of a hymnbook or any other guide. Kierkegaard’s Moravian upbringing would have given him a rich understanding of hymnody.

Kierkegaard gravestone with Brorson Poem. PHOTO: Mark Safstrom

Kierkegaard kept drawing on this rich resource of Brorson’s pious songs throughout his writing career. Among his works you can find references to Brorson in Eighteen Upbuilding Discourses, Stages on Life’s Way, The Point of View, and Practice in Christianity. Brorson’s influence is perhaps most evident by Kierkegaard’s allowing the hymn writer to get the final word on his life. This bit from a Brorson hymn is what Kierkegaard asked to have placed on his gravestone.

In yet a little while

I shall have won;

Then the whole fight

Will at all at once be done

Then I may rest

In bowers of roses

And perpetually

And perpetually

Speak with my Jesus.9

IV. Kierkegaard’s Critique of Pietism

And what were Kierkegaard’s views of the Pietist movement itself? Kierkegaard criticizes the Pietists in Copenhagen for being too legalistic and too distracted by moralistic crusades. Kierkegaard sounds deeply pained and embarrassed by his faith heritage. Part of growing up in the church is learning to differentiate between hypocrisy and authenticity. Kierkegaard pokes and prods at the Pietists like an insider, not an outsider.

It will be made to seem as if I wanted to introduce pietism, petty and pusillanimous renunciation in things that do not matter. No, thank you, I have never made the slightest gesture in this direction. What I want to incite in the direction of becoming ethical characters, witnesses of the truth, of willing to suffer for truth and to renounce worldly shrewdness.10

Are these the words of a man who rejects the heartfelt faith and pious desires of his childhood? Certainly not! Søren Kierkegaard doesn’t shake his fist at the heavens and reject God like his father Michael. The younger Kierkegaard rejects the false piety and hypocrisy of putting on a religious show by rejecting the theater and dancing. Søren Kierkegaard rejects the worldly shrewdness of religious leaders picking a fight with theaters and dance houses. He counters with his own pious desire for ethical character, speaking the truth, and accepting the way of the cross. This is an authentically pious critique of the pettiness of what passed for Pietism in Copenhagen.

V. Kierkegaard’s Praise of Pietism

Finally, we conclude with Kierkegaard’s praise of Pietism. Kierkegaard’s kind words about Pietism are no more definitive than his critique. Kierkegaard asserts that Pietism is the singular and certain consequence of Christianity. Then Kierkegaard postulates such a heavenly vision for Pietism that it cannot possibly be experienced in our fallen world.

Yes, indeed, pietism (properly understood, not simply in the sense of abstaining from dancing and such externals, no, in the sense of witnessing for the truth and suffering for it, together with the understanding that suffering in this world belongs to being a Christian, and that a shrewd and secular conformity with this world is unchristian) — yes, indeed, pietism is the one and only consequence of Christianity. And the mildest suggestion, it seems to me, is that we at least put up with its being said, without thereby judging anyone, but directing every individual, including me, to grace and indulgence.11

No Christian movement, certainly not Pietism, has managed to function very long without passing judgment. Christians, especially the pious and upstanding, are always vulnerable to the temptation of judging sins, virtues, clergy, lay leaders, budgets, hymns, and praise songs. Christians, especially the pious and upstanding, forget their daily need for grace and forgiveness. Christians, especially the most upstanding believers, presume they can skip the suffering of the cross. Kierkegaard praises pious desires that cannot possibly be institutionalized. For Kierkegaard, Pietism is the logical consequence of Christianity, but never fully realized even in the Pietist movement.

Kierkegaard gives us a helpful corrective to any rose-tinted understanding of historical Pietism. The Pietist movement was never free of impious judgment and shrewd secularity. Many of us are keen to look idealistically on Pietism in order to praise lay Bible studies, relevant preaching, and heartfelt conversions to Jesus. Those pious practices remain worthwhile, but they are not techniques that allow Christians to manage the Holy Spirit and congregational renewal.

In truth, the historic Pietists could be just as moralistic and hypocritical as modern churchgoers. Kierkegaard refuses to fit comfortably into the definition of Pietism, because his ideals simply will not defer to the reality of Christian life together. Kierkegaard’s radical understanding of Christian faith only works because he never resorted to taking his backup job as a parish pastor, where judgment calls are necessary.

Kierkegaard’s high Christology works because of his low ecclesiology. Kierkegaard’s lonely voice cried out in the wilderness in an inflammatory and offensive manner. Just as the Pietists were irritants to the State Church of Denmark, Kierkegaard was a gadfly to both State Church Lutherans and Pietists. Kierkegaard believed in pious renewal, but he also saw modern Pharisees obstructing new life in Christ. Kierkegaard believed Jesus “appears again and again in Christendom; to put it briefly, it is the collision of Pietism with the established order.”12

Søren Kierkegaard owes a great debt to Pietism. His personal Christian faith was shaped by his Pietist family history, reading, and singing. Kierkegaard had good reason to be embarrassed by the hypocrisy and judgmentalism of the Pietism movement in Denmark. He also had good reason to identify Pietism as a natural consequence of Christianity. Kierkegaard was a product of Pietism, and ironically, the Pietist value of individualism kept him from belonging to the movement. Kierkegaard was a Pietist prophet, formed by the heartfelt faith, but more comfortable in the wilderness outside the movement in order to critique its pharisaical tendencies.

1. Kirmmse, Kierkegaard in Golden-Age Denmark, 34.

2. Burgess, “Kierkegaard, Brorson, and Moravian Music,” 242.

3. Thulstrup, “Pietism,” 184.

4. Thulstrup, “Pietism,” 184

5. Kierkegaard, Journals and Papers, Vol. 3, 524, X3 A 682 n.d., 1850.

6. Kierkegaard, Letters and Documents, Vol. 3, 524, X4 A 94 n.d., 1851.

7. Kierkegaard, Letters and Documents, Vol. 3, 524, X4 A 94 n.d., 1851.

8. Thulstrup, “Pietism,” 201.

9. Burgess, “Kierkegaard, Brorson and Moravian Music,” 215.

10. Kierkegaard, Letters and Documents, Vol. 3, X3 A 556 n.d., 1850.

11. Kierkegaard, Letters and Documents, X3 A 437 n.d., 1850

12. Kierkegaard, Practice in Christianity, 86.

REFERENCES

Burgess, Andrew J. “Kierkegaard, Brorson, and Moravian Music.” International Kierkegaard Commentary Volume 20: Practice in Christianity. Edited by Robert Perkins. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2004.

Cumulative Index to Kierkegaard’s Writings. Edited by Nathaniel Hong et. al., Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press, 2000.

Hong, Howard V. & Hong, Edna H. (eds.). Practice in Christianity. Princeton University Press, 1991.

Kirmmse, Bruce H. Kierkegaard in Golden-Age Denmark. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1990.

Thulstrup, Marie Mikulova. “Studies of Pietists, Mystics, and Church Fathers.” Bibliotheca Kierkegaardiana vol. 1, Kierkegaard’s View of Christianity. Editors Niels Thulstrup and Marie Mikulova Thulstrup. Copenhagen C.A. Reitzels Boghandel A/S, 1978.

Thulstrup, Marie Mikulova. “Pietism.” Bibliotheca Kierkegaardiana vol. 6, Kierkegaard and the Great Traditions. Editors Niels Thulstrup and Marie Mikulova Thulstrup. Copenhagen C.A. Reitzels Boghandel A/S, 1981.

Søren Kierkegaard’s Journals and Papers. Edited and translated by Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong. Bloomington and London: Indiana University Press, 1978.