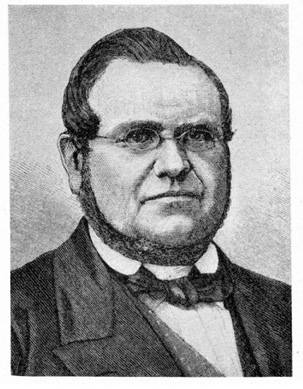

Oscar Ahnfelt: Troubadour of the Swedish revival

For most of my life, I had noticed Oscar Ahnfelt’s name in hymnals as the writer of tunes. I learned those hymns and they were some of my favorites. As my interest in Swedish hymnody grew in the last decade, I became increasingly curious about the Ahnfelt story. I acquired two Ahnfelt song CDs published in Sweden, which launched my interest and fed my curiosity into his life. These recordings are “Blott en dag” (“Day by Day”) by Carola (1998) and “Andeliga Sånger av Lina Sandell och Oscar Ahnfelt” (“Spiritual Songs by Lina Sandell and Oscar Ahnfelt”), with songs recorded in the 1960s by the Gothenburg Chamber Choir and soloists.

Ahnfelt had amazing abilities as a singer, musician and evangelist, and had a significant impact on the 19th-century Swedish revival. Three aspects of his story fascinate me in particular. The first are his extensive tours throughout Sweden, Norway and Denmark, in which he preached, sang and played his guitar. The second is the amazing way that God worked through George Scott’s ministry in Stockholm to prepare Ahnfelt and Carl Olof Rosenius for their respective ministries. And the third were several significant women who collaborated with Ahnfelt and amplified the reach of his ministry: Clara Ahnfelt, Jenny Lind, and Lina Sandell.

Oscar Ahnfelt was born into a Lutheran pastor’s home in Gullarp, in the Skåne province Sweden, in 1813, the youngest of seven children.1 He was taught by his older brothers. He grew up in a home environment with a mother who loved music, encouraged singing and playing musical instruments. Ahnfelt had friends with whom he sang in a quartet. The Ahnfelts lived just a few miles from Lund University, so pastors, professors, and lecturers would often stop by the house for hospitality, conversation, and even the occasional musical performance.

When he was 26, Ahnfelt moved to Stockholm to study at the Academy of Music. There he was shocked to find Stockholm to be a spiritually dry place, yet eventually he found his way to George Scott’s “English Church.” Scott was a Scottish Methodist revival preacher who was called in 1830 to move to Stockholm to minister to the English workers employed by Samuel Owen.2 Scott was a dynamic and energetic pastor who was an expert at networking. He felt a burden to address the culture of rampant alcoholism in Sweden at the time, as well as to push back against the century-old ban on conventicles, or small group Bible studies. The scope of Scott’s ministry soon expanded from serving English workers to also reviving and renewing the Church of Sweden after he began holding revival services in Swedish. This ultimately led to him traveling to America and England to raise funds for his Swedish ministry. He also successfully networked with many influential leaders in government and in the Church of Sweden.3

As a foreign pastor, Scott’s Swedish revival work in Stockholm was ambiguous. As a foreigner, he had the right to practice his own faith and preach to his countrymen in Sweden, but his preaching to Swedes was viewed as problematic. His critical comments made abroad about alcoholism and other issues of Swedish society also aroused opposition. Due to protests and riots, Scott was forced to leave Sweden in early 1842. Scott’s exit from Sweden could have been a deathblow to his ministry and the publication of Pietisten (The Pietist), which had only recently started, had he not enlisted the help of Carl Olof Rosenius.

Rosenius grew up in a pastor’s home in northern Sweden. He was involved in various revival activities in his teens, and had a conversion experience at age 15. Upon beginning theological study in Uppsala, Rosenius experienced spiritual coldness and also poor health. Disappointed, Rosenius returned to Stockholm in 1839 and found work as a tutor. While there he had a severe crisis of faith and sought out George Scott for counsel and guidance. A close friendship developed and Rosenius was invited to work with Scott in his Swedish ministry. Rosenius had found his call to ministry. In April 1841, Rosenius preached his first sermon at the English Church. When Scott traveled abroad to America and Britain for six months that year to raise support, Rosenius preached and took on new leadership roles with Pietisten.

When Ahnfelt moved to Stockholm and began to attend the English Church, he encountered Rosenius. A close friendship developed, and Ahnfelt provided music at Rosenius’s meetings. On Easter Sunday in 1841, Ahnfelt experienced a spiritual breakthrough. Rosenius was leading the worship and preaching. Rosenius recognized Ahnfelt’s spiritual and musical gifts, and they would be close friends and ministry partners for life. Øivind Tønnesen’s biography of Ahnfelt includes the texts of some of the correspondence between Rosenius and Ahnfelt.

Although Rosenius had traveled in the past to conduct revival meetings, his new role publishing Christian literature left him without the spare time to travel. He encouraged Ahnfelt to develop his preaching skills, in addition to his music ministry. To get Ahnfelt started, Rosenius sometimes left meetings early, which left Ahnfelt with no choice, but to talk and pray and close the meeting.

Rosenius’s encouragement to Ahnfelt further into ministry led to a time of discernment for him. His biographer writes of a darkness that came over Ahnfelt around this time as he weighed the possible paths of his life. His options were to continue teaching and performing music as part of the Royal Academy — a life of performing and receiving applause — or to follow God’s call being fully committed to the ministry. After much anguish, he chose the vocation of an evangelist and was once again joyful.

In 1845, in response to requests of Rosenius to hold revival meetings, he sent Ahnfelt to answer the call of ministry trips to the provinces of Västergötland and Norrland. Afterward, additional requests came from all corners of the country for Ahnfelt to come and conduct revival services. Ahnfelt developed into a successful evangelist and lay preacher. Once started, these continuous “Macedonian calls” were received at Pietisten and became Ahnfelt’s “marching orders.”

Ahnfelt eventually would hold revivals in other Scandinavian countries, including a number of preaching trips to Copenhagen. Starting in 1853, Ahnfelt made trips to Norway where he filled a thousand-seat venue in Oslo, Norway, night after night. Tønnesen reflects in his book on Ahnfelt how Norway, as a nation, was probably more open than Sweden was to Ahnfelt’s ministry, and his book contains many descriptions of places and events where Ahnfelt’s preaching was particularly effective. The extent of these travels is astounding, given transportation at the time.

Ahnfelt is known for a signature 10-string guitar that was his traveling companion throughout his years of revival meetings. It was a “harp” guitar, which is characterized by a guitar-based instrument with additional unstopped strings that can accommodate individual plucking. Ahnfelt worked with one of the prominent harp guitar makers of the time, Otto Fredrik Selling, who worked in Stockholm between 1850 and 1875. For a look at examples of these guitars, one can compare the photos of Ahnfelt’s guitar with the photos of Selling’s guitar on the Harp Guitar website.4

Clara Strömberg was part of the Rosenius fellowship and a conventicle participant. She was an integral supporter of the Swedish revival early on. Oscar met Clara at a conventicle meeting where he sang. In 1844 they were married and Clara became a vital lifetime partner and support in Oscar’s work. The couple had two children, both of whom died young. This was a heavy sorrow that they shared. They moved to Karlshamn where they had many friends and supporters. While Oscar led evangelistic meetings, Clara conducted missionary activities at the Seaman’s Mission.

As Oscar Ahnfelt composed revival tunes and sang them, he desired to print them so the messages and songs could stay with his listeners. Through his involvement at the Academy of Music in Stockholm, he met Swedish renowned opera singer Jenny Lind, who was a participant and supporter of the revival. She sang Sandell/Ahnfelt songs at her concerts and other events. In 1850, in response to Ahnfelt’s request, Lind gave him money to print his first book entitled Andeliga Sånger (“Spiritual Songs”). This led to him eventually producing 12 editions of his ever-growing songbook that was created over three decades and came to contain 200 songs. Many of these song books traveled with Swedish immigrants to America.

Lina Sandell

Lina Sandell was another key player in the Swedish revival and in Ahnfelt’s ministry. She was the editor of devotional publications for a revival organization within the Church of Sweden, the EFS. Ahnfelt became aware of the giftedness of Sandell first through her poetry published in devotional newspapers. By 1850, he was composing tunes to accompany Sandell’s verse and using them in his revival services. Sandell became one of Ahnfelt’s primary sources of texts for his music ministry. Sandell said that Ahnfelt had taken her verses and “sang them into the hearts of Swedes.”5

Ahnfelt could be persistent asking for new material, and Sandell wondered how she got any peace when he was in Stockholm. She even wrote special lyrics when Ahnfelt needed a song for a special occasion. The Conventicle Edict had been in place in Sweden since 1726 to prohibit Bible studies outside the state church without a state church pastor present. Ahnfelt faced resistance and roadblocks to his evangelist meetings. His response was unwavering because of his conviction that he had to obey God’s call rather than prohibitions put in place by humans. At one of his revival meetings, a warden interrupted the gathering and warned the participants they could face punishment for participating in the illegal meeting. Ahnfelt stated that he must continue to declare God’s word. He warned the audience that they could leave if they wanted to, but no one left. Rosenius railed against the evil of religious persecution, complaining that counselors, bailiffs, and judges had become purely specialists in religious persecution. At one time Ahnfelt had seven courts with various charges against him, and it was said that there were days when he would go from a court hearing to a revival meeting in the same day.

Ahnfelt had a stubborn quality that allowed him to outlast those who opposed his ministry. Once a local priest denied Ahnfelt entrance into his parish church. Ahnfelt sat down on the front step and began to play his guitar. A crowd gathered around to listen. The priest ultimately relented.

There were some creative responses by people caught attending illegal conventicles. One account is of an 1853 gathering in Älvdalen of 31 people who met in a house for prayer and Bible study. When the sheriff came by to check on the meeting, they began singing a hymn, which was not illegal: hymn number 26 in Sions Nya Sånger (“New Songs of Zion”), “Ack helga dag, du marterstund” (“Alas, holy day, hour of martyrdom”). They proceeded to sing all 54 verses at a slow pace. When they finished the last verse, they began singing verse first again, ready to sing all 54 verses a second time. When the sheriff realized what they were doing, he gave up and left.6

There were other legendary strategies to avoid trouble. Besides having their Bibles, they would have whiskey bottles and playing cards close at hand. If the meeting was interrupted by the authorities, they would hide the Bibles and bring out the whiskey bottles and playing cards so that the warden could see that they were “fine Christians.”

Ahnfelt faced police harassment, court appearances, and resistance from state church pastors who opposed his revival work. At one point, complaints were brought to King Karl XV. The king replied that he wanted to hear Ahnfelt in person before making a decision. Realizing the immense importance of such a performance, Ahnfelt allegedly contacted Lina Sandell to write a special song for him to perform before the king, “Vem klappar?” (“Who knocks?”). When he played and sang for the king, tears filled the king’s eyes. When the song ended, the king proclaimed, “you may sing as much as you desire in both of my kingdoms,” referring to Sweden and Norway.7

In conclusion, Oscar Ahnfelt’s evangelistic ministry was the spiritual balm that many Swedes longed for in the mid-19th century. Hymns such as “Day by Day” still convey a warm and comforting message. People would listen to him preach for hours and come back the next night to sing new songs that reflected the yearnings of the listeners. His unique style of singing with his harp guitar contributed to a musical richness to the revival gatherings. Although Ahnfelt’s ministry took place in a far away place and time, without him many of Lina Sandell’s poems and verses may have never made it beyond her spiritual poetry notebook. If not for Jenny Lind, there may not have been 12 editions of Andeliga Sånger printed and used in the Swedish revivals, and which made their way with Swedish immigrants into America to carry the message of this hymnody to future generations. The sentiments in these songs have given a voice of comfort that many of us continue to cherish.

Below is one of Ahnfelt’s favorite hymns that he cherished later in life, and which is included in the Covenant Church’s first hymnal, Sions Basun (“Trumpet of Zion”) in 1908.

No. 663 - “O jag vet ett land”

O jag vet ett land långt från sorg och strid,

Där hos Gud är idel ostörd frid.

Därvid flodens strand livets träd ock stå,

Med en härlig tolvfald frukt uppå.

Detta sköna land är Guds vänners land, Ja, mitt eget sälla fadersland (2x).

“O, I Know a Country” (free-verse translation)Vad ej öga sett, vad ej öra hört,

Ej i mänskohjärta än sig rört.

Det har Gud beredt dem i hemmet där,

Som af hjärtat honom älska här.

Detta sköna land är Guds vänners land, Ja, mitt eget sälla fadersland (2x).

O, I know a country far from sorrow and strife,

Where with God there is blissful, uninterrupted peace.

There by the riverbank where the tree of life stands,

With a beautiful twelve-fold fruit upon.

This beautiful country is the land of God’s friends, Yes, my own blessed fatherland (2x).

What no eye has seen, what no ear has heard,

No human heart can yet imagine.

What God has prepared for them there in that home,

For those who love him here.

This beautiful country is the land of God’s friends, Yes, my own blessed fatherland (2x).

1. Unless otherwise noted, biographical information is drawn from Øivind Tønnesen, Oscar Ahnfelt: Evangeliets Trubadur (1952).

2. Karl A. Olsson, By One Spirit (1962).

3. Kjell Söderberg, “Carl Olof Rosenius and Swedish Emigration to America,” translated by Dean M. Apel (2021).

4. Hans Bernskiöld, “Oscar Ahnfelt (1813−1882)” (2015), on www.levandemusikarv.se; for images of these guitars, see, “History of Harp Guitars,” www.harpguitars.net/history/makers.htm.

5. Tønnesen, Oscar Ahnfelt.

6. Torgny Erséus, “Om väckelsens musik,” in CD jacket for “Andeliga Sånger av Lina Sandell och Oscar Ahnfelt” (1996).

7. J. Irving Erickson, Twice Born Hymns (1976).