F.O. Nilsson and the Swedish Baptists

In 2008, the Baptist General Conference (BGC) rebranded itself as “Converge Worldwide,” which the denomination refers to as its “movement name” (an expression as perplexing as the new name itself). One can hope that this will be a short-lived experiment in consumer marketing. Until 1945, the Baptist General Conference was the Swedish Baptist General Conference of America (or, as its early members knew it, Svenska Baptisternas i Amerika Allmänna Konferens.) It is interesting that BGC churches today should be so hesitant to identify themselves as Baptists given the hardships that their forebears endured for doing exactly that. The life of one of the first Swedish Baptists, Fredrik Olaus Nilsson, was characterized by determination in the face of opposition.

After founding a Baptist church in 1848—the first successful “free church” in Sweden—F.O. Nilsson would be arrested, imprisoned, and banished from his country. Baptists were unpopular not only with the authorities, but also with their neighbors. In 1850, Nilsson and fellow Baptists were gathered in a private home to celebrate communion when, according to Nilsson’s account, a mob broke into the house with “sticks, clubs, guns [and] knives” and then ”kicked and struck” the worshippers before hauling Nilsson away to the district sheriff, who promptly put him in jail.

At the time, to hold any kind of religious meeting involving anyone beyond the members of one’s immediate family in any place other than the Church of Sweden was illegal. This had been the case since 1726, when parliament had passed the Conventicle Act, a measure aimed at reducing the influence of Pietism. The clergy considered grassroots religious movements a threat to order, sound doctrine and, no doubt, their authority. It was not lost on critics of the Conventicle Act at the time that drunken carousing with your neighbors was legal, but inviting them over for Bible study was not. The law was applied selectively, but Nilsson had clearly run afoul of it, and his unlikely role as a nonconformist religious leader would serve as a catalyst in Sweden’s slow movement toward embracing religious liberty.

Nilsson was born in 1809 to the family of a merchant sea captain in the province of Halland on Sweden’s west coast. He was the grandson of sea captains on both sides of his family. His mother died before he was seven, ending what had been a stable family life. His father quickly slipped into debt, and he and his three brothers were separated. As a young man, he found work as a sailor aboard merchant vessels that would take him across the Atlantic. By the mid-1830s, he was a crewmember aboard an American ship that sailed between New York and Charleston. On one journey, the ship was caught in a terrible storm near Cape Hatteras, causing Nilsson to turn his attention heavenward. Describing the storm years later, he wrote, “It appeared as if the hand of the Almighty held me by the hair over the opened hell in order to plunge me, in the next moment, down into the abyss.” The experience was not unlike that of Martin Luther, who had vowed to become a monk after living through a terrifying thunderstorm.

The ship survived the storm, and, after its safe arrival in New York, Nilsson found his way to a Manhattan congregation that would become the First Mariners’ Baptist Church. Although he had not yet become a Baptist, he was determined to pursue a life of religious devotion and spent the next few years employed by the New York Tract Society as a colporteur. By 1839, he was back in Sweden traveling as an independent preacher. After meeting the well-connected Scottish Methodist evangelist George Scott at a temperance meeting in Jönköping in 1840, Nilsson received a commission from the American Seaman’s Friend Society to serve as a missionary to sailors in the port of Gothenburg. He would also work in Sweden for the British and Foreign Bible Society. The Protestant missionary activity funded from abroad to spread the Gospel in Lutheran Sweden was surprisingly extensive.

In 1845, the same year that he married Ulrica Sofia Olson, Nilsson met Gustaf Schröder (also known as Gustavus Schroeder), a well-traveled Swedish sea captain who had been baptized by immersion in New York’s East River the previous year. Schröder introduced Nilsson to formal Baptist theology, and soon thereafter Nilsson began a correspondence with the German Baptist minister J.G. Oncken. Convinced by the Baptist arguments that baptism should reflect a conscious profession of faith and be expressed by full immersion in water, Nilsson traveled to Hamburg to meet Oncken, who baptized him in the Elbe River on August 1, 1847.

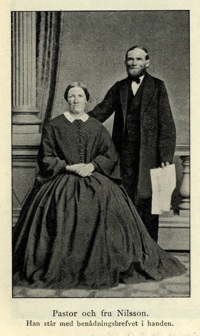

The following year, Nilsson invited the Danish Baptist pastor A.P. Förster to his native province of Halland, where Förster baptized Nilsson’s wife, two of his brothers, and two other men in the sea at Vallersvik on September 21, 1848. Förster quietly returned to Denmark, leaving the six Swedes to organize their country’s first Baptist congregation. Nilsson would soon make a trip to Hamburg to be formally ordained as a Baptist minister. By the spring of 1849, the little Swedish Baptist church had 35 members. The following year, Nilsson encountered the aforementioned mob and subsequently was tried and sentenced to banishment for spreading false dogma. In 1851, he applied directly to the king for mercy, but King Oscar I would not lift the sentence. Nilsson went to Copenhagen in exile. Given his numerous international connections, it is perhaps not surprising that Nilsson’s banishment received international press attention, much of it brimming with criticism of the Swedish government.

By 1853, there were more than 50 professing Swedish Baptists enduring censure and, in some cases, the forced baptism of their infant children. That year, a group of at least 17 joined a small flock of Danish Baptists who had decided to emigrate to America with Nilsson and his wife aboard the American ship Jenny Pitts. After arriving in New York, they proceeded to Chicago, where the Danes turned north to Wisconsin, and the Swedes continued westward to Rock Island, Illinois. Rock Island was already home to the first Swedish Baptist church in America, founded in 1852 by the immigrant schoolteacher-turned-Baptist-minister Gustaf Palmquist. Some of the group moved on to Houston in Minnesota Territory and organized a Baptist church there. Nilsson would spend the next several years in Illinois, Iowa, and (from 1855 to 1860) in the Scandia settlement in Carver County, Minnesota.

He established a farm in Scandia, but traveled widely to preach, helping to organize a handful of Swedish Baptist churches and even made an impression on his German neighbors, at least two of whom he baptized. In Minnetrista, he helped to establish the first German Baptist church in Minnesota in 1859. The following year, the 25th Street Baptist Church in New York called Nilsson to be its missionary to Scandinavia, and he accepted. In September 1860, he and Ulrica returned to Sweden despite his banishment. Oscar I had died in 1859, so Nilsson sent an appeal to the new king, Carl XV, in the hope that his sentence would be rescinded. Before the end of the year, the king declared that Nilsson’s banishment was over. That year, for the first time, it became legal for Swedish citizens to leave the Church of Sweden, so long as they joined another Christian body acknowledged by the government, and only after they had met their Lutheran parish priest for counseling.

His case had been a source of bad publicity for the government and, it seems, good publicity for the Baptists. While Nilsson had been in America, the Baptists in Sweden had grown to 4,500 members. He took a leadership position at the Baptists’ national conference in Stockholm in 1861 and shortly thereafter organized the First Baptist Church of Gothenburg, where he served as pastor for seven years. But it may have proven frustrating for Nilsson to have returned to the large, organized community of Baptists that had grown up in his absence. The leadership of the movement was now largely in others’ hands in Stockholm, while he labored in Sweden’s second city. He ultimately decided to return to the United States. With the proceeds from the sale of his farm in Minnesota (forwarded to him in Sweden), he bought passage back to America.

The final chapter of Nilsson’s life is surprising. In 1869, when he was 60 years old, he and his wife settled in Houston, Minnesota, where they joined the Swedish Baptist church that had been founded by immigrants who had traveled with them to America 16 years earlier. They had returned to a changed country, where more than 600,000 Americans had died in the Civil War. Nilsson served intermittently as pastor of the church in Houston until 1876, when 13 members left to organize a new church in protest over Nilsson’s evolving theological views. He had been reading the work of Theodore Parker, a prominent Transcendentalist who denied the reliability of the Bible, and apparently had begun to question the divinity of Christ. He expressed his new opinions in print, finding himself again in opposition to those around him, but this time alienating many of those who had once stood with him.

Swedish Baptist historians have wrestled with this phase of Nilsson’s life, but take comfort in a letter that he penned to a friend four days before he died in 1881. He wrote (to quote from L.J. Ahlstrom’s translation): “Have had great temptations to forsake everything in religion. But the Lord is faithful and will not let us be tempted beyond our strength. With him is grace and love. Jesus Christ is my only hope, on that Rock will I rest, who has saved me. May the Lord help me to the last.”

F.O. Nilsson, the sailor who turned evangelist, and then Baptist minister, prisoner, exile, immigrant, farmer and freethinker planted the seeds that grew into the Baptist Union of Sweden, just as the churches that he shepherded in America grew into the Baptist General Conference. Today, the descendants of those Baptists on both sides of the Atlantic face identity crises, as the Americans re-brand themselves, and the Swedes prepare to merge their denomination with those of the Mission Covenant Church and the Methodist Church of Sweden. The working name for the new denomination in Sweden is Gemensam Framtid (“Common Future”), which perhaps makes more sense than “Converge Worldwide,” but still rings a bit hollow.

Further Reading:

L.J. Ahlstrom, Eighty Years of Swedish Baptist Work in Iowa, 1853-1933 (Des Moines: Swedish Baptist Conference of Iowa, 1933).

J. Byström, En frikyrklig banbrytare: F.O. Nilssons lif och verksamhet, 2nd ed. (Stockholm: Trynings-kommitténs förlagsexpedition, 1911).

Adolf Olson, A Centenary History as Related to the Baptist General Conference of America (Chicago: Baptist Conference Press, 1952).