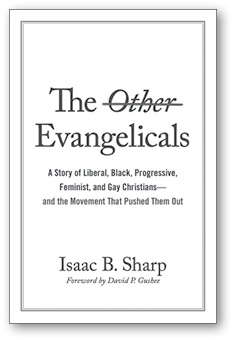

A Pietist's Bookshelf

The Other Evangelicals: A Story of Liberal, Black, Progressive, Feminist and Gay Christians—And the Movement That Pushed Them Out

Isaac B. Sharp

Eerdmans, 2023

Reading Isaac Sharp’s The Other Evangelicals was like revisiting my entire life. Although he begins with the fundamentalist/modernist debate of the early 20th century, the focus of the book is upon the post-World War II neo-evangelical movement. The contentious efforts to define and delimit evangelicalism, to say who was in and who was out, were all quite familiar, and in some cases, painfully familiar to me. My life crossed paths with many of the persons named in the book. I have vivid memories of evangelist Tom Skinner electrifying a group of high school students at a “mission conference” I attended as a sixteen-year-old. During the conference a group of us, mostly kids from the South, sat at a table with Skinner after lunch and asked questions for hours. He was patient with us and our undoubtedly painful questions. It was a moment of awakening for me. Some years later, another prominent African American evangelical, Bill Pannell, would speak at my Bible school and play basketball with a group of us. I was at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School shortly after Jim Wallis (whom I would later meet through evangelical/Jewish dialogue) and was an avid reader of the early Sojourners, as well as The Priscilla Papers (a Christian feminist magazine), and The Other Side. By the time I arrived at North Park Theological Seminary in 1981, the late Donald Dayton was no longer on the faculty, but I would get to know him later (by odd coincidence, although I never met her, I was in the same doctoral program at Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary with his ex-wife Lucille Sider-Dayton).

Every crisis, every conflict in Sharp’s book was familiar to me. In addition to growing up in an evangelical church, attending an evangelical Bible school, and evangelical seminary, I served on staff with InterVarsity Christian Fellowship. I had a subscription to Christianity Today and followed the twists and turns of the “battle for the Bible,” the quest for women to serve as pastors, and the rising questions and anxieties about race, abortion, and homosexuality. And at every point, or so it seemed to me, someone was trying to define me out of evangelicalism. At every new movement of liberation, the gatekeepers, financial and otherwise, as Sharp makes clear, closed ranks and declared their opponents “not real evangelicals.” Any individual, any school, any denomination that took a “wrong turn” on the handful of issues important to the big E evangelicals had to be silenced or, as the subtitle puts it, “pushed out.” The current identity crisis within evangelicalism, with thousands being “pushed out”—engaging in a process of “deconstruction” or simply leaving the faith altogether—is clearly rooted in the anxiety of the gatekeepers to preserve their understanding of evangelical identity, as well as their own power and the resources to preserve that power. What is the source of this understanding of evangelical identity?

A key section of Sharp’s superb book comes early on when he discusses the conflict between church historian George Marsden and North Park’s Donald Dayton. Marsden is famous for his Fundamentalism and the American Culture and many other books making a case for a particular understanding of evangelical identity. Dayton argued that Marsden was viewing evangelicalism “through a ‘Presbyterian paradigm’ which interpreted evangelicalism primarily as a conservative, dogmatic, defense of orthodoxy in the face of liberalism.” Marsden distorted evangelicalism by reading it “in an almost exclusively Reformed-Calvinist light” giving more credit and power than was due to the mostly Calvinist-Reformed evangelical gatekeepers. Dayton argued for a “Pentecostal paradigm” that understood evangelicalism“ not as a rationalistic response to liberalism but instead as an innovative, Spirit-filled disruption to the stodgy conservatism of the traditional church.” This was evangelicalism from below as opposed to the evangelicalism from above of the Calvinist elites. One of Dayton’s significant concerns was that this standard “Presbyterian paradigm” “that existed by the latter half of the twentieth century had swallowed up smaller, older, more coherent denominational traditions—like his own Wesleyan-Holiness tradition—extinguished their important theological distinctives, imposed a generically conservative, lowest-common-denominator viewpoint on everything labeled evangelical and thereby ruined everything it touched.” It is not difficult see here the tragedy of the Evangelical Covenant Church whose distinctive and profound Pietist heritage has been battered almost beyond recognition, however contemporary leadership seeks to claim it—when it is convenient.

One sees this, of course, not just within the Covenant Church. The contemporary Southern Baptist Church has become a parody of its Baptist heritage. Where are the once defiant advocates for the separation of church and state? Where are the disciples of “soul competence” or even congregational polity? And since when were Baptists strict Calvinists? I even heard a Baptist leader claim that Baptists were “confessional.” I told him “confessional Baptist” sounded rather like “free church Catholic.” He laughed. And one could ask the same questions of so many churches within the holiness tradition so beloved of Donald Dayton. So many today are pale reflections of what the tradition once was. So many are that “lowest-common-denominator” evangelicalism Dayton so rightly feared. Dayton, it seems to me, won the battle with Marsden, but in the end, tragically, Dayton, and all of us have lost the war.

How did we get here? In part, that is the burden of Sharp’s book, but I want to highlight a couple of key issues. The real concern hiding beneath the various issues like abortion, homosexuality, and women in ministry really had nothing to do with those issues. Rather, the real concern was how to understand the authority of the scripture. The earliest fundamentalists imagined that claiming the “inerrancy of scripture” would somehow protect the church from the baleful effects of “liberalism.” Few appeared to have noticed that a high view of scripture had not prevented the Protestant movement from dividing into tens of thousands of denominations, all claiming a high view of scripture. The guilty secret here is that the claim for inerrancy was grounded in an unexamined rationalistic hermeneutic. Albert Schweitzer suggested that the 19th-century scholars who searched for the historical Jesus had looked down the well of history for the face of Jesus, but had seen their own face and mistaken it for his. In this case, I would suggest, the 20th-century neo-evangelicals looked down the well of scripture for their preferred meaning, saw it reflected there and mistook it for the Word of God. As I suggested to students over the years, the problem with fundamentalism is that it is modernist. It requires a commitment to a rationalistic hermeneutic, a scion of Scottish common-sense realism that will produce the outcome it desires based on the illusion of unimpeachable reason.

Over the final decades of the 20th century and the first decades of the 21st, Sharp shows how group after group, individual after individual attempted to claim and hold their evangelical identity, only to be told they were not “true evangelicals.” Consider the case of Ralph Blair. I must confess that I had never heard of Ralph Blair until I read Sharp’s book. In retrospect I suppose that is not surprising. Blair was converted in high school, and, remarkably, came to terms with being both gay and Christian even hoping that he could be in a committed relationship with another man someday. He went to Bob Jones University and was kicked out, not for being gay, but for speaking favorably of Billy Graham. He would go on to attend Dallas Theological Seminary, Westminster Theological Seminary, and pursue graduate work at the University of Southern California. He would eventually join the staff of the same campus group I served, InterVarsity Christian Fellowship. They would fire him when they learned that he was convinced one could be an evangelical Christian and in a committed gay relationship. In 1975 he founded Evangelicals Concerned, an organization dedicated to promoting a ministry of reconciliation and support for gay Christians. The organization, which still exists, offers counseling, workshops, conferences, and resources in support of gay Christians. Blair, who is still alive, has insisted that his is an evangelical faith however opposed some are to his understanding of sexuality. Examples like Blair could be multiplied for each of the issues Sharp discusses.

There are in the mystical tradition two approaches to God. There is the apophatic approach and the cataphatic approach. The apophatic says you cannot make positive statements about God. You cannot say what God is, you can only say what God is not. The cataphatic approach to the contrary says you can state positive propositions about God. By analogy, I would suggest that the problem with evangelicalism is that it has chosen an apophatic approach to defining its identity—you cannot say what evangelicalism is, you can only say what it is not! You cannot be an evangelical and support abortion, or gay marriage, or female pastors, or the Democratic party, or be “woke,” or not vote for Donald Trump—or vote for Donald Trump; or be a Christian nationalist, or not be a Christian nationalist; or support Israel or not support Israel. And so on.

The cataphatic approach, I would argue, asks the same question our Pietist forebears asked: Are you alive in Jesus? The Pietists of the 1600s, weary of post-Reformation battles, argued for a cease fire. Not that they thought theology unimportant, but just not central. To love and follow Jesus; to revere and listen for what the Spirit says to the churches through the scriptures; to serve the poor, oppressed, and lost: these were the keys to evangelical faith. Dare we hope for a pietistic revival?