‘Christ’ and ‘Jesus’: Parties in the church

Over a half century ago, as the winter sun slanted through windows slightly opaque with Chicago grime, Professor Donald Frisk lectured in a Nyvall Hall classroom at North Park Seminary. The subject in his Systematic Theology course that day was less systematic than historical: the range and variety of Christian experience and thought over 2,000 years. One of the most important of the persistent distinctions among Christians, Frisk said, fell between those who usually tended to speak of “Jesus” and those who did so of “Christ.” People who thought and spoke more often of Jesus saw him primarily as a teacher and example; those who thought and spoke more often of Christ viewed him as Lord and Savior. The differing emphases were, of course, not mutually exclusive, Frisk cautioned, but they did point to important distinctions that had characterized two millennia of Christian history.

Sitting in that class, I thought of the Jefferson Bible, the third American president’s attempt to extract from the canonical New Testament what he regarded as the essence of the plain but profound moral teachings of Jesus. Jefferson sought a Christianity untrammeled by the textual accretions of wonders and hard sayings that troubled, even confounded, American rational deists like him. He preferred the Galilean peasant whose life and teachings still inspired folk and who needed neither mystery nor miracle to validate moral and religious experience. Jefferson’s spirit ran through the liberal American Social Gospel that was preached from the Methodist and Congregational pulpits of the mainline churches in the suburban upstate New York town where I spent some of my high school years church shopping — before I fell into the conservative Bible- believing fellowship of the Evangelical Covenant Church on the corner of Kenmore and Harvest Avenues on Buffalo’s north side.

From the party in the apostolic church led by Peter, which saw Jesus as the fulfillment of the moral and ethical precepts of Old Testament Judaism, through the age of the Reformation, down to the social gospel of 20th century American Christianity, the Church has never wanted for those who have found the primary meaning of Jesus to be as a great teacher and example, the greatest moral force in human history whose life perfectly matched his teachings.

This emphasis or interpretation of the Gospel has a counterbalance in those who see Christ primarily as Lord and Savior. In this kind of Christianity, one that usually speaks of “Christ,” the Palestinian peasant Jesus is understood to have existed with God the Father before all time and space. His life, death and resurrection are believed to constitute an event that has changed the very nature of the cosmos, of all reality itself. Through that Christ event the broken relationship between God and humanity has been repaired — “God and sinners reconciled,” as Charles Wesley’s Christmas hymn says. No person, save one at peace with God through Christ, can hope to live up to the moral precepts of Jesus.

Those who think of Jesus the Teacher and Example have been sometimes put off by that “cosmic” understanding of Christ the Lord and Savior. Martin Luther is thought to have rediscovered the Pauline emphasis upon salvation through faith in the Christ whose death and resurrection altered the relationship between God and humanity. But not every reformer in the 16th century took that view of Christianity. In the 1520s Luther engaged in a classic debate with the humanist Erasmus who, rather than viewing Christianity as centered in justification by faith, believed it to be a philosophy of life, a moral path set forth by the life of Jesus, one which a person could choose to follow by an act of intellect and will.

The deists of the 18th century, Thomas Jefferson among them, argued for a universe governed by the laws of nature. They found suspension of those laws, as in miracles like those in the New Testament or asserted through church history, to contradict reason and good sense. Often people who tend in the same direction as those rationalists of the 18th century Enlightenment see the complicated theological thought of St. Paul as the progenitor of an emphasis that has changed the simple moral life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth related in the Gospels into the cosmic theological Christ of Paul or Luther.

The physician, organist and theologian Albert Schweitzer, one of the great humanitarian icons of the mid-20th century, also found universal ethical meaning in Jesus’ example and teaching, spending his life in Africa as a medical missionary. The contemporary American literary scholar Harold Bloom writes that one can sift through all the authentic Pauline materials in the New Testament and find no evidence that their author knew that Jesus, like his Old Testament prophetic predecessors, was especially concerned for the poor, the outcast and the sick. Charles Freeman, a contemporary British scholar, reminds us that Paul is the single major Christian theologian never to have read the Gospels.

The strand of interpretation represented by Erasmus or Jefferson, Schweitzer or Bloom, is, accordingly, not so much attracted to Paul and his idea of the Christ who changed the very set-up of the universe. Such interpreters are often put off by the fact that Paul rarely speaks of “Jesus” without calling him in the same breath “Christ,” and that there is in fact little evidence in the Pauline materials of any familiarity with Jesus’ own life and teachings. Sometimes one encounters in modern scholars who contrast the Jesus of the synoptic Gospels with the Christ of Paul’s letters the idea that it was the latter, Paul, who was the real deviser of the system that came to be understood as “Christianity.” Those who are especially troubled by this are apt to view Paul as the “concocting genius of Christianity.”

Yet there are difficulties in the idea that Paul, decades after Jesus, turned the simple gospel of Jesus into a metaphysical system with Christ at its center. One of the most important of these difficulties is simply that the oldest writings in the New Testament include the letters of Paul. Of course, when it comes to drawing up a list of which specific epistles are certainly written by Paul, scholars differ.

But even if you limit the genuine Pauline letters to Romans, I and II Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, I Thessalonians, and Philemon, as stricter scholars such as the American Catholic John Dominic Crossan or the Scotch Methodist James Dunn do, you have in the Pauline materials documents from the first century decades of the fifties and sixties. These probably pre-date (or, as some conservative scholars maintain, were written at the same time as) the present synoptic Gospels, Matthew, Mark and Luke. Of course the synoptics clearly depend upon earlier source materials, and their roots lie close to Jesus’ life itself. But if it was Paul who devised Christ-centered Christianity, he did so at the same time as the gospels were being drawn up.

So the letters of Paul are the oldest extant materials in the New Testament at hand (or are certainly among them), even when the list is cut to the seven epistles mentioned above. That means that in the first decades of Christian history theological speculation about the meaning of the life of Jesus had already begun. In Paul this became a cosmic interpretation of the Christ event. Very quickly the simple Palestinian peasant whom Jefferson, Schweitzer, et al, so admired began to be seen as a figure who changed the very nature of universal reality, and especially of the divine-human relationship.

Within a few decades the man who preached the Sermon on the Mount and gave his peasant followers the parables was understood to be the one who, when a person had faith in him, brought eternal salvation. The barriers between Jews and Gentiles were held to be broken down by him, as were the divides between men and women, wealthy and poor.

Faith in him was believed to give a person victory over death and sin.

Christ alone had divine power to enable his followers to emulate him and live up to his teachings; his was not a way of life that a person could simply decide by force of his own will to follow. Pauline Christianity held a rather pessimistic view of human nature, believing that only through Christ could one become a new person. The view which other Christians have held is more sanguine about the possibility of a person deciding for her- or himself – by an act of will – to turn to following Jesus; this view of human possibility is somewhat more optimistic.

In any case, during the century after Jesus the church began to adopt the concepts and vocabulary of Greek philosophy to explain the meaning of his life and work. Within three centuries orthodoxy attributed to Christ a divine nature equal to that of God the Father, using the Greek concept of “essence” or “substance” to do so. Thus the Nicene Creed speaks of Christ being “of one substance with the Father.” The “high Christology” with which Paul had interpreted the event of Jesus had become an amalgam of biblical thought and a philosophy from the Greco-Roman world. This was not an interpretation of Jesus’ life present in the first three gospels, though the Gospel of John, usually dated decades later than the first three gospels, did see Christ as having eternally pre-existed with God.

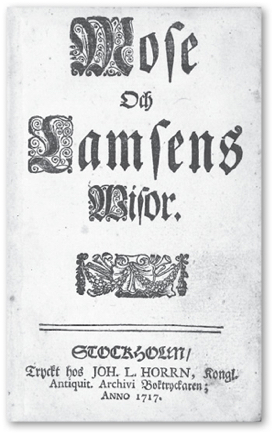

These differing emphases upon Christ or upon Jesus run through the modern church life which Pietisten readers may be familiar. Scholars have noted that in the 19th century, the Church of Sweden used the 1819 hymnal by Johan Olof Wallin, which some Pietists felt portrayed Jesus merely as an ethical model and smacked of rationalism. Instead, these Pietists preferred collections like “Songs of Moses and the Lamb” (Mose och Lambsens wisor), where Christ was regarded as the divine savior. And this difference was one aspect of the troubles that roiled the American Covenant Church during the 20th century. The pietistic stress upon personal experience and upon each person’s obligation to interpret the Scripture for her- or himself left some of the Mission Friends free to emphasize the life of Jesus as a pattern for his followers to live up to and others equally free to hold that only Christ, the divine-human being, could free one from the sin that otherwise spelled eternal doom.

The Augustana Synod, which determinedly insisted upon creedal orthodoxy, tended toward stressing Christ as Lord and Savior. For example, in the 1920s, O.J. Johnson, President of Gustavus Adolphus College, declared that, “The crucial moment of modern youth” had arrived. “It must decide whether to accept Christ as a guide and teacher or, as the Bible declares him to be, a Savior.” Johnson understood the issue; for him knowing Jesus as guide and teacher was not enough.

You need only reflect on your own experience to realize that in the course of a life spent in the precincts of the church, one encounters both emphases among Christian friends. One of mine wrote to me a few years ago that he had “always been more inclined to say ‘Christ’ than ‘Jesus.’” Another told me recently that he was weary of theological hair-splitting: “I am a simple person trying to live as the man from Nazareth lived!”

What I want to emphasize here is just that from its earliest days Christianity has found both mindsets in its midst. An elevated view of Christ, a “high Christology,” is not something imposed decades later on the simple original gospel by a reformed tent-maker who never met Jesus except on the road to Damascus. Rather, from its earliest days elements within the church, beginning with Paul, put the life of Jesus into a context far wider than the roads and towns of Palestine in which he lived.

And at the same time, to ignore the effort to understand and emulate the moral and ethical meaning of Jesus’ life, in the certainty that one is saved by one’s orthodox theology, is to fall into an error from which Pietism sought to free the churches of northern Europe, strangled, the Pietists felt, by “orthodoxy.” It seems to me clear that apostolic Christianity made both emphases, sometimes simultaneously, and sometimes in differing factions within the early church. Professor Frisk’s distinction has a 2,000-year history. I think I can still hear his soft clear voice on the second floor of Nyvall Hall, spelling out types of Christianity that have persisted for two millennia.