Travelling With Ellen — Reprt from Ecuador II

Ellen Bergstrom is a student at Luther College in Decorah, Iowa. She spent a semester in Ecuador. This is the second of two articles about her time there. —Ed.

One of the first things that struck me in the Houston airport, arriving in the United States after five months in Ecuador (besides my amazement at how fast everyone walks and the wonders of clean public bathrooms where it is possible to actually flush the toilet paper), was all the different types of people. There were so many blonde people, black people, Asian people, and even a few people with bright pink or blue dyed hair and piercings. I no longer stuck out whatsoever in a crowd. I was even suddenly kind of short again. At 5' 7" I had felt like a giant in Ecuador.

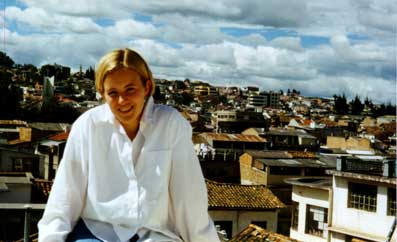

Ellen on a balcony of her school in the Cuenca

Born and raised in Minnesota with blonde hair and Swedish features, it was definitely a new experience for me to be a racial and cultural minority in South America. While most people were very friendly and nice and I never encountered any hostility, I did run into plenty of stereotypes and unequal treatment. I was able to watch how people changed their behavior when interacting with me in contrast to my Ecuadorian friends. Servers in restaurants sometimes switched to awkward English when addressing me, not believing that I would understand Spanish. Cab drivers and shopkeepers always doubled or tripled their prices. My Ecuadorian friends were constantly mistaken as my tour guides. Guys on the streets made all kinds of interesting comments and proposals. Beggars and children sometimes flocked to me to ask for dollars. I got lots of stares ranging from wary to calculating to just plain curious. Many people in Ecuador (and, I believe, in other places around the world) see all Americans as camera-snapping tourists with little knowledge about the language or the culture, extremely rich with money to throw away, and just out to have a good time with little regard to morals. Even though I could see how that reputation is often deserved, it was uncomfortable and frustrating to be judged on first glance and lumped in with all the rest. I worked hard to try to prove that I didn’t fit the stereotype.

Diversity among Ecuadorians, at least to the untrained eye, is not apparent. Most have the same basic color hair, eyes, and skin. However, I quickly learned that this tiny country is incredibly diverse. Ecuador is about the same size as Arizona but it has three completely different zones that sharply divide the country—the coast, the Andes mountains, and the rainforest. Each is like a different world, and each has its own distinctive culture— different dress, food, traditions, and different Spanish. The regions have different accents and slightly different vocabulary. While I was there, I learned to pick out five or six distinctive accents, but native speakers can distinguish a dozen or so. There are about 10 distinctive indigenous groups in the mountain region alone, each with its own dress and traditions. In addition, there are indigenous groups in other parts of the country, the African-American cultures, and the main mestizo culture.

Even in all this diversity, I stuck out like a sore thumb and sometimes really felt like the outsider I was. The best way I found to fight the ugly American tourist stereotypes and to bridge the gap between cultures was to take the time to get into conversations with people, to ask questions, to listen, to observe, and to smile. This turned out to be my favorite thing in travelling. I got to know so many interesting people. I quickly formed deep friendships with my host family who had a wonderful sense of humor and a very warm, welcoming, and fun-loving attitude. I met a lot of people through their extended family and circle of friends, all middle-class mestizos, well-educated with professional jobs and comfortable homes. I also got to know Maria, a sweet, shy, young indigenous woman from Otavalo, who had been living with a few relatives in a cramped apartment in Cuenca since age 15, selling crafts in the market. She grew up speaking Quichua, and as she still speaks it with her friends and family in the market, her Spanish is sometimes a little rusty. I got to know Masias, who owns a little store/restaurant and works two other jobs to support his family and Sisa, an indigenous woman from Saraguro. She is an extremely intelligent university professor and author, who still wears her traditional clothing and somehow lives on a salary of $46 a month. I met sophisticated university students from Quito, many of whom had studied or travelled in the United States and Europe, and spoke several languages fluently. I met a group of hippies on the beach who travel up and down the coast, with only a few dollars in their pockets, selling artwork and jewelry. In the rainforest, I met our guide José, who grew up there and was part of the Quichua tribe. We stopped our canoe along the river so that he could pick up something from his parents’ thatched hut home, and we chatted with his dad on shore, amongst the tropical plants, thick mosquitoes, and roaming chickens. On the coast we hung out with a group of tour guides on vacation, talked with a professional fisherman, learned some new card games from a group of kids, and went swimming in the ocean with some local girls. I also had unforgettable conversations with cab drivers, waitresses, and a group of six shoe-shine kids in Cuenca’s main square to whom I paid the unheard-of price of $2 after their half-hour of fancy cleaning and shining of my shoes.

I had so much fun getting to hear everyone’s stories and learning about their experiences, backgrounds, and cultures while sharing some of mine. I learned much about myself in the experience and much from them.

One thing that struck me about Ecuadorians in is how they carry on calmly in a country that often seems on the edge of chaos. No matter how bad things get, what inconveniences come up, or what goes wrong, they make do and keep a positive attitude. I don’t think many Type A personalities survive in Ecuador. Keeping an agenda is impossible. Delays and obstacles are to be expected, but Ecuadorians just keep trying without getting frustrated. When the power or running water goes out (because of too little or too much rain), people carry on as best they can without much complaining, until it is fixed. When rockslides or transportation strikes block the road, people figure out a way around or they walk to work. Even when the presidency was overthrown for a brief time by a military coup and there were riots in the streets, most people just shook their heads and carried on. It’s not that people don’t care, but they recognize when things are beyond their control and make the best of it. I believe it makes people a lot less stressed and less likely to take things for granted.

People seemed to look on the bright side. Through all the problems with the economy, the corruption, the natural disasters, etc., they do not dwell on the negative. On the contrary, Ecuadorians look for a cause for celebration. A minor holiday is cause for a parade and a family event is an excuse for a big get-together. Even if it seems as though they don’t have anything, they always seem to have enough to share with family and friends in celebration of the happy things that happen in life.

My first experience as a minority was eye-opening, but learning to overstep those stereotypes and the boundaries that separate us was very rewarding. I heard amazing stories, compared differences, discovered many similarities, and learned a lot about myself, including some things about how I would like to be.