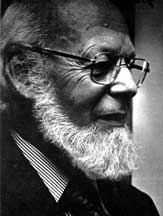

Sigurd Westberg

March 31, 1910 to October 3, 1999

Sigurd Westberg was a much-loved grandfather, father, and father-in-law. Though his achievements were outstanding, his commitment to family was at the center of his life. Four daughters, their husbands, and their families remember Sig with great affection. Sandy Marks, one of the sons-in-law said that "the brothers-in-law club was one of his biggest fans."

So this modest man with his remarkably irenic spirit has left the company of his family and community. Marks said: "For those who knew and loved Sigurd Westberg, his life continues not only through memories but through the inspiration and guidance of his exemplary life. If I have ever met God in the flesh, it was in the dignity, the humor, the creativity, the presence, the love, and the grace of Sigurd Westberg." Pietisten is pleased to print the tribute below by Fred Holmgren, given at the memorial service. — Ed.

An Appreciation

In ancient Jewish literature, there are a number of stories about thirty-six righteous persons who inhabit every generation. These people are witnesses of God’s presence in this world. By their true speech and righteous actions, they preserve the health of the smaller community and the larger society. The identity of these people is hidden from others—and even from themselves—but their hidden existence keeps the world in balance.

I am reminded of these stories when I think of Sigurd Westberg. Sigurd was well-known, but his modesty often hid from view his extraordinary gifts and accomplishments. Like the thirty-six righteous persons, Sigurd was a source of health and goodness in our community and in the wider world. He had a heart for those bearing burdens, and he was one who also truly enjoyed the happiness and achievements of others. When someone would share with him a success story, Sigurd would typically flash a big smile, shake his bearded head to the side and say something like, "That’s just great!" Then he would ask, "How did it happen?" and would listen to the whole story.

Sigurd was a gentleman—pronounced "Gentle Man"—but no push-over. He was a person of conviction and had ample resources to present his point of view persuasively—but always with a courtesy that left the discussion open.

I was fortunate to be at North Park Seminary during Sigurd’s tenure. What a person to work with—stimulating, considerate, and understanding. He was an excellent choice for Professor of Missions. The nineteen years he and Ruth served together in Zaire/Congo made him aware of important issues that missionaries face in witnessing to the Gospel. Significantly, he called one of his foundation courses in Missions: "Christian Confrontation with World Religions." This title reflected his Christian commitment, but also his own character of witness, that is, a dialogical witness in which Christian identity was maintained while being fair to and respectful of other faiths.

Sig was a reader—a habit he said he picked up when he was a missionary. His interest in books and articles was frequently reflected in discussions by means of the phrase, "The other day I read…." Then he would make his statement. And his reading was remarkably varied. It included topics ranging from automobile hubcaps to politics to the character of the universe. He seemed to be well-informed about nearly every topic that came up for discussion. Sig’s habit of reading—and the curiosity that drove this habit—was recognized by the University of Chicago, which, in an unusual action, allowed him to bypass the undergraduate B. A. degree to move on to the graduate degree of Master of Arts.

Sig was also a reader of the Scripture and for -eighteen years he and a British colleague were occupied with the translation of the Bible into Lingala, the dominant trade language in Zaire. This translation was underway while he was a Seminary professor. It was a demanding task requiring not only an expert knowledge of Lingala, Hebrew, Greek, and Latin but also an acquaintance with many contemporary western languages. Of these latter, he had, of course, thorough knowledge of French, German, and Swedish. As a translator, he was required to examine carefully every text of the Bible. The knowledge gained from his translation work enabled him to offer critiques of a number of contemporary translations of Scripture. For example, he wrote to the publisher, Thomas Nelson and Sons, to call attention to several mis-translations in the Revised Standard Version of the Bible. Prof. Luther Weigle of Yale University, Chairman of the Translation Committee, responded with a thank you letter indicating that in future printings these errors would be corrected.

Sigurd also kept himself informed about political issues and, from time to time, expressed his views to public officials or in the news media. In 1969 and 70, for example, he addressed letters of protest to President Richard Nixon, Senators Charles Percy, and Ralph Tyler Smith, as well as to Representative Roman Puchinski, regarding the Kent State incident when a number of protesting university students were fired on and killed by the National Guard. He defended the right of students to demonstrate without fear of violent response and reproached the government for not listening to the student protests. He added: "These young people are right!"

Further, he sent a letter to Christianity Today which had published an editorial about Angela Davis and Communism. Sigurd, ever fair and concerned to be correct in details, protested what he considered to be a too simple depiction of Communism. He did take the caution to say that he was not a communist!

Sigurd had a gentle, clever sense of humor. He enjoyed telling of the time a little boy’s eyes locked on him as he strode by the child and his mother. The child was noticeably impressed with Sigurd’s white hair and beard. He turned to his mother and said, "Momma, there’s Santa Claus." Sigurd bent over to the child and whispered, "Shhhh, don’t tell anybody."

I have always enjoyed remembering another incident. In 1976, I spent a sabbatical in Cincinnati at the Hebrew Union College Jewish Institute of Religion. One day, when tired of research, I thought of Sigurd doing his archival work in Chicago. I wrote him a playful note but addressed it to The Archivist, North Park Theological Seminary. In the note, I identified myself as a retired Lutheran professor who wished to make a gift of the Martin Luther Bible dated 1517 to the Archives. I indicated that if he wished to receive this gift he should write me immediately—but then, purposely, did not provide him a return address. I signed the letter, I.M.A. Logner. Logner in German means liar, therefore: Prof. I-am-a-Liar. The next week I received a letter addressed to Prof. I.M.A. Logner, in care of Fredrick Holmgren. Checking the postal address on the envelope, Sigurd learned that the letter was sent from Cincinnati and had a good suspicion that it was from me. In his letter, he thanked Prof. Logner for the gracious offer of the 1517 Luther Bible, but noted that the Covenant Archives already had two such Bibles—in addition to the handwritten copy of Martin Luther himself.

There is so much more to be said about Sigurd Westberg—and much more will be said as people who knew him meet and speak together.

Sigurd Westberg was a person of faith and intellect—human and humane—one who shared his rich life with us and gifted us memories that rejoice the heart!