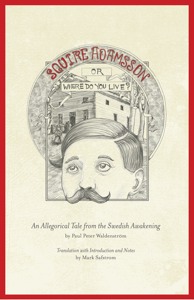

Squire Adamsson: Or, Where Do You Live?

First written in 1862-63 and revised in several subsequent editions, Squire Adamsson was one of the most widely read Swedish novels in the second half of the 19th century. The author, Paul Peter Waldenström (1838-1917), was then a young student in Uppsala, and would later go on to be an influential preacher, critiquing the religious practice of the Lutheran state church and founding the Mission Covenant Church of Sweden. The heroine of the novel is Mother Simple, who assists Adamsson in his journey toward understanding the limitless nature of God’s grace. Several of the themes in this novel build on concepts within Lutheran Pietism as popularized by Spener, Francke, Zinzendorf and C.O. Rosenius, particularly the nature of God’s grace, congregational polity, and the practice of faith. Furthermore, Waldenström’s emphasis on the subjective experience of faith bears similarity to notions of temptation (anfäktelse) articulated by both Luther and Kierkegaard. This new English translation of Squire Adamsson is published by the devotional journal Pietisten in honor of the 150th anniversary of the novel. The translation was completed by Mark Safstrom, lecturer in Swedish at the University of Illinois, and features extensive notes and a scholarly introduction. The novel is introduced by Gracia Grindal, professor emeritus of rhetoric at Luther Seminary.

Buy the Book

Buy the the printed book - $24.99

Buy the the printed book and eBook bundle - $29.99

Buy the Kindle Edition - $9.99

Foreword

The Narrow Path

by Gracia Grindal

My pastor father and mother, serving in the Lutheran Free Church, a small pietistic Norwegian American Lutheran Church, loved to tell the story of a new family in town. The family belonged to an even smaller Norwegian pietistic church body, and had to go shopping for another Lutheran church because there was no congregation in town from their denomination. As Lutheran Pietists they believed strongly that Christians were to separate themselves out from the world, and that to be a Christian was to stand firmly against it. The pastor of the largest Norwegian Lutheran congregation in town came to them and said, “You will want to join our church because everyone belongs to it!” The couple reacted in horror. Such a congregation was the last sort of church they wanted to join, they said, to the puzzlement of the pastor. It was a failure to understand another culture, but more than that, evidence of a great divide, unbridgeable, between the two pieties. (Of such misunderstandings came many jokes in our parsonage!)

They might as well have been speaking two completely different languages. The gulf between the pastor and the couple is the conflict that Waldenström and his readers know in their bones: Is one a Christian simply because one is Swedish and part of the state church? Ernst Troeltsch (1865-1923) described the difference in his morphologies of religious groups as a “sect type,” since the sect type emphasizes faith as a decision, believing that the normal beginning of genuine Christian life is spiritual transformation through explicit commitment to Christ and taking responsibility for one’s life in moral terms. Lutherans historically have been both church types and sect types because of the pietistic traditions from which many of the Lutheran immigrants to this country tended to be, especially the Scandinavians.

I thought of that story many times while reading Squire Adamsson. For those who understand the “language of Canaan” this book will be easy reading—they will understand what is being said, almost like the secret code that tells everything when a believer in Scandinavia hears the answer to the question, “Are you a believer?” (“Er du troende?”) If you answer, “Of course, I go to church,” your inquirer will know exactly what you are saying, but you will have no idea that they have just heard you say, “I am not a Christian.” I grew up in such a version of Norwegian-American Lutheran pietism, much influenced by Hauge’s revival in Norway and softened some by Carl Olof Rosenius, whom my Grandfather Grindal read for daily devotions along with Bishop Laache, Norway’s chief exponent of Rosenius’ teachings. While I do know my grandparents read Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyan, whom some could say was the inspiration for Squire Adamsson, I would not be a bit surprised if they had also read this book. Even though as Americans the Scandinavian state church was not our reality, it lingered in our minds. We knew people who practiced a kind of “churchianity,” as we called it, rather than Christianity. They would be puzzled when a young person in their midst would return from Bible camp, Young Life, or FCA, with the testimony, “Although I was baptized and confirmed a Lutheran, it wasn’t until [some experience] that I came to know Jesus as my personal Savior.”

It is still a staple testimony of those who have come to faith through an experience of conversion or an awakening of their baptismal faith. Many Lutherans think that such a statement is somewhat unseemly, and yet it lurks in most Lutheran traditions in America, especially in my part of the Norwegian-American Lutheran tradition. Even though we did not insist on an experience of salvation, we knew it well. We knew faithful Christians who had remained in their baptismal covenant, but also rejoiced at conversions. God could work in many ways, but talk of conversion troubled other Lutherans, especially those from other Lutheran traditions, like Eastern and Missourian Lutherans. Conversion? That’s Baptist! It did not sound, nor look Lutheran to them. We Norwegians made our peace with each other as Norwegian Lutherans in the Madison Agreement of 1912, which said one could be an orthodox Lutheran and not resolve the argument, but value both orthodoxy and pietism as expressions of the faith. Although contested by some, it brought most of the Norwegian Lutherans in this country together in 1917 when they formed the Norwegian Evangelical Lutheran Church, later simply the ELC. The agreement and the tolerance of the theology of conversion that the Norwegians accepted have always stuck in the craw of the other Lutherans in this country as not being Lutheran. The Haugean pietist in me, however, understands the agreement in my bones. As does the Swedish Augustana Lutheran Pietist one would find at the Lutheran Bible Institute, or those among our best friends, Swedish Covenanters. We, after all, began our lives in this country together in the Scandinavian Augustana Synod (1860-1870) until the Norwegians and Danes broke away to form their own seminaries—Augsburg and Augustana. (My part of the Norwegian Lutherans always says, with regret, we merged with the wrong Swedes!) We have always understood, with Luther, whom we read with affection and delight, that faith is not knowledge or ritual, it is a living, breathing, active relationship with Jesus that sets one against the world.

Those Lutherans who understand the language of Canaan, most often Pietists, will know the city named World and the city named Holiness, the bookkeeper Conscience (a nice picture) and the city named Evangelium. They may even feel a slight needling at the Mission Society in one area of the City, Sanctification, where the Workshop for the Redeemed keeps people busy doing good. They have met Shepherd-for-Hire, they grew up with Squire Adamsson, and will know why he changes his name to Abrahamsson and then Hagarsson. They know exactly why Mother Simple grows concerned for him, and even why she feels that Immanuel has abandoned her in what Luther would have called the dark night of the soul. They will hear biblical verses and stories referenced naturally as the way people spoke to one another of their common lives. People in these traditions uttered themselves biblically because it was the language they spent their time reading and speaking. And they knew when they were being reproved or upbraided. Waldenström’s book has sharp teeth that cut at all religious and pious delusions. No matter whether one is a church or sect type, one is always surprised by one’s own foibles, or sins.

Mother Simple, like many pious women in my background, is the voice of the true Christian, calling back, reproving, encouraging, speaking the truth. One thinks of Lina Sandell, whom the leaders of the Swedish revival knew would be a spiritual leader from her childhood on, or of Kristine in the first part of Bo Giertz,’ Hammer of God, who is able to bring peace to the dying man when the young seminary graduate could not. They are, however, not without their own spiritual struggles and terrors, all of which devout Christians know and fear.

This is an edifying and cautionary tale for awakened Christians (and maybe for those church types trying to figure them out) to watch for all the ditches along the narrow way, from lukewarm Christianity that wants to sue for peace with the world to intellectualizing the faith, to works that try to hide the lack of faith, to other enthusiasms we delude ourselves with as we live both in and outside the church. There are dragons on all sides, and only Immanuel can save us. Mother Simple knows that and teaches us that the Christian life is not onward and upward, but daily ups and downs, lapses and successes, that turn us toward Immanuel. Faith in him assures that we are counted as righteous, nothing else. Waldenström knew where all the dragons lay in wait, and his book is an edifying guide on our way.